Middle Son (Area of Detail)

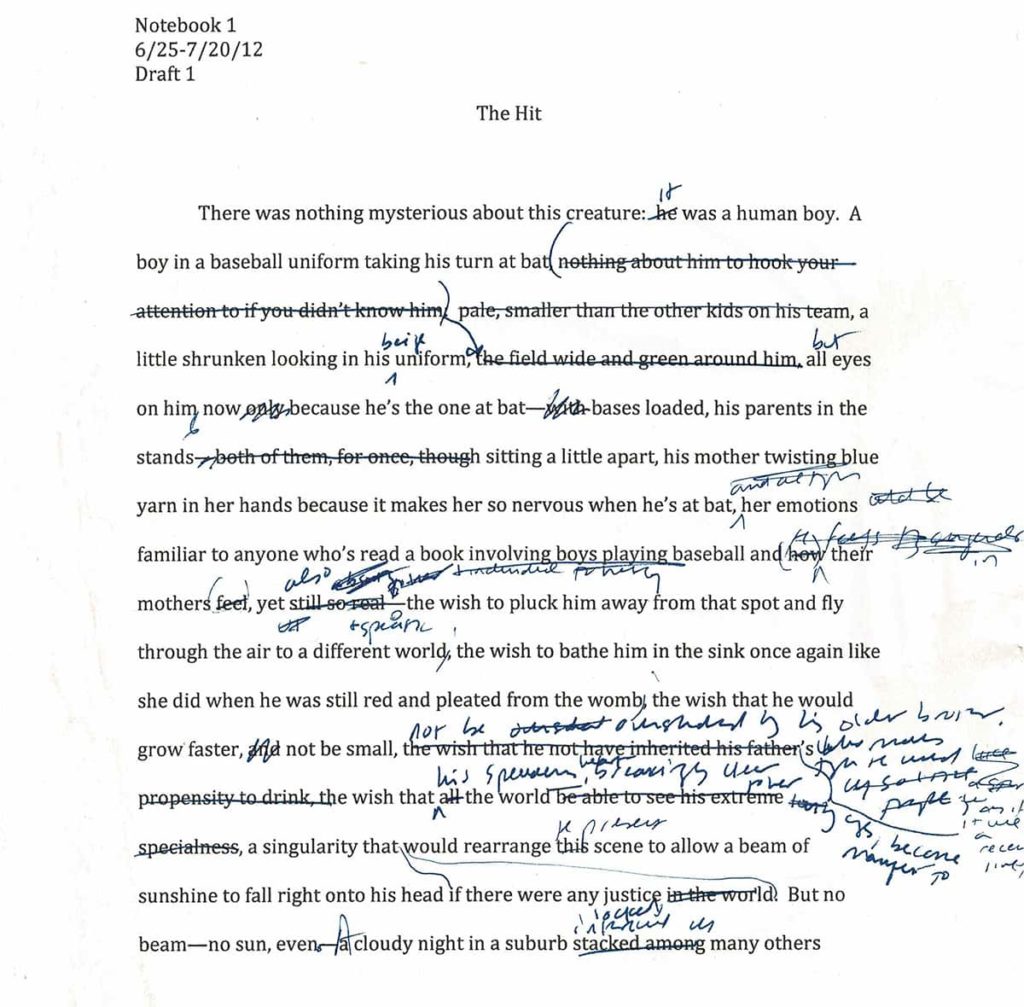

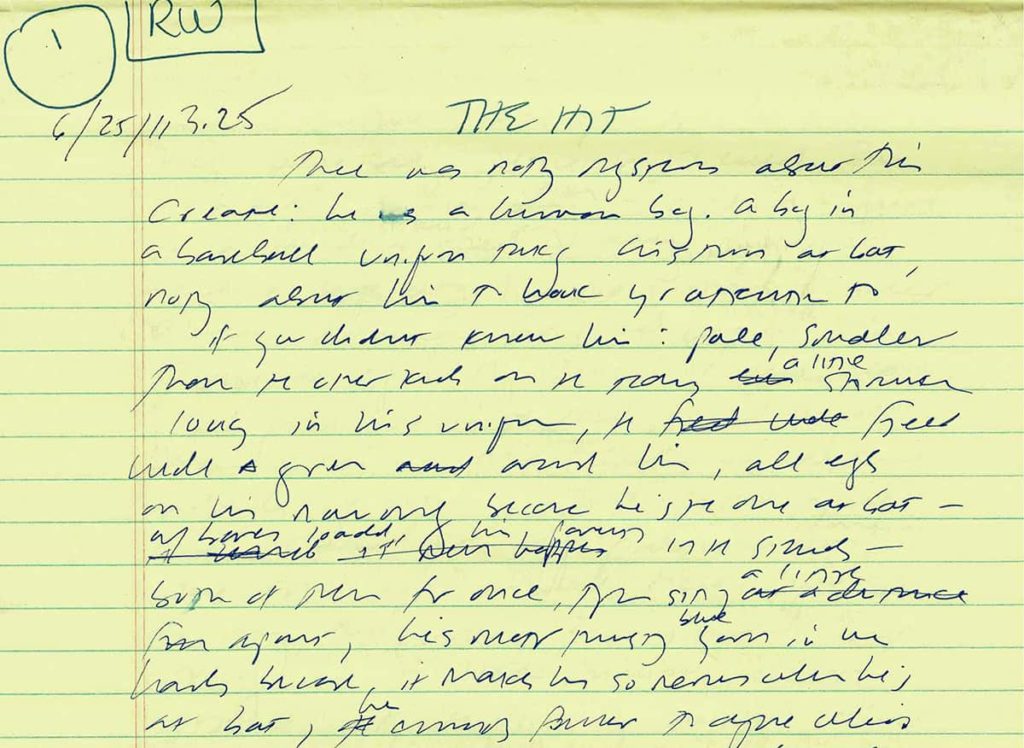

There’s no mystery about this creature: a human boy. Eleven years old, a little shrunken-looking in his beige uniform, nothing to hook your gaze if he isn’t your brother or son, but all eyes on him now because he’s the one at bat, bases loaded, his parents and two brothers in the stands, his mother wringing a lump of yarn because it’s agony watching him hit (or try to hit, he never hits), her emotions cliché to anyone who’s read a book or seen a movie about children playing sports and how their mothers feel, and yet—how is this possible?—fiercely specific: a wish to pluck him from that spot and spirit him away to a place where she can protect him; a craving to hold him like she did when he was newly born and smelled like milk (his first smile, a tiny sputter of lightning across his face, a thing she often recalls); a hope that he won’t be dwarfed forever by his older brother, who moves through the world as if it were a receiving line; a plea to someone, something, that her boy’s uniqueness, so manifest to her lovestruck eyes, be revealed to all: a singularity that, were there justice in the world, would rearrange the present scene and cause a beam of light to fall directly onto his head.

But no beam—no sun, even. A cloudy dusk in late spring in an Upstate New York suburb interlocked with many others, around a city like many other cities. At night, from the window of a plane, their lights look like seams of gold ore in black rock. And among the tens of thousands of suburbs surrounding some three thousand American cities, there might be, from April onward, seven or eight hundred boys standing at home plate at any particular time, each emulating the batting stance of whatever hero’s poster hangs above his bed, and a throng of parents, some ringing cowbells, some getting nasty—stories of bad parental behavior are part of a picture that turns generic the instant you cease to have a stake in it, as in: The boy at bat is your boy.

His name is Ames Hollander. Middle son, squashed between godliness above and eccentricity below. People forget his name. They forget he exists—that he can see and hear and remember like they can. His mother frets, knitting the brown V-neck sweater he’ll reject in winter when she presents it to him (No one wears knitted sweaters, Mom!): How can the love and dread she feels for her middle son be converted into something tangible, something that can help him?

One horror of motherhood lies in the moments when she can see both the exquisiteness of her child and his utter inconsequence to others. There are so many boys in the world. From a distance they look alike even to her, especially in uniform.

It’s 1991, and a lot of things that are about to happen haven’t happened yet. The screens that everyone will hold twenty years from now haven’t been invented, and their bulky, sluggish predecessors have yet to break the surface of ordinary life. No one in this crowd has ever seen a portable phone, which gives to this moment the quality of a pause. All these parents gathered in the fading light, and not a single face underlit by a bluish glow! They’re all here, in one place, their attention burning toward home plate…